Building a Build System

January 2026

Rust, Rain

I have been inspired to build a build system. I want something that integrates closely with continuous integration with simplicity and caching by design. As part of this I decided to build a custom programming language. I chose the name rain. The Rain language is simple and functional. It must understand enough to be able to cache function calls, track file changes and dependencies on outside state.

This is inspired by Bazel, Rust, Go, Haskell, Make, Docker, Python, and TypeScript.

I am building this for my own learning and interest so it is not production quality. I also only work on the parts that I find useful or rewarding so some parts may be underdeveloped.

Rain Language

A Rain source file contains a set of declarations that can be in any order. Declarations are named values that are evaluated lazily. This means that declarations can reference other declarations irrespective of the order they are written in. This even works across imports, meaning a circular import is not an error. If a declaration forms an infinite recursion by referencing itself or a chain of references forms a loop, the call stack limit will be reached.

Memoization

A simple Fibonacci example using the memoization built into the language.

let std = stdlib("0.9.1")

let { Integer } = std.types

let main = fn() {

fib_result = fib(40)

std.print(fib_result)

}

let fib = fn(n: Integer) -> Integer {

if n <= 0 {

0

} else if n == 1 {

1

} else {

fib(n - 1) + fib(n - 2)

}

}

This is not a very efficient algorithm to compute the Fibonacci sequence because it duplicates a lot of work. However, because Rain automatically caches the function calls to fib, it computes reasonably quickly. In this case the fib function only relies on n and doesn't have any side-effects so it is easy to cache.

Files

Rain tries to keep all functions pure and without side effects. So dealing with files presents a difficulty. The filesystem is by design is a large global state that is difficult to track in user space. This is handled by defining a concept of a file area. A file area is essentially a root directory i.e. its parent cannot be accessed. File areas come in two kinds: local and generated.

A generated file area is created by Rain and considered read-only after it is created. This allows functions that use generated file areas to be cached based on the file area id since they cannot change.

Local file areas are modelled as external files to Rain that can change between Rain invocations but are assumed to be stable within a given invocation. When running Rain in a checked out local git repository, this will automatically create a local area with the contents of the repository. Caching functions that depend on a local file area is trickier as the file must be checked if it has changed.

let std = stdlib("0.9.1")

let main = fn() {

local_zip = std.fs.relative_file("area.zip")

unzipped_area = std.compression.extract_zip(local_zip)

inner_file = std.fs.file(unzipped_area, "inner.rain")

std.fs.size(inner_file)

}

In this example the source file is in a local area and so area.zip is resolved in the same area. When the area.zip is extracted, it is extracted into a new generated area and the inner.rain file is found inside this area.

Imports

Importing other Rain source files is actually very simple. There is an internal import function that takes a File and returns a Module. A module is a lazily evaluated set of declarations. This allows for import cycles and importing files from external places such as archives, git repositories and URLs. This would be a bit verbose to use so the actual import function is syntax sugar based on the caller's module_file. This simplified import syntax will resolve the file in the current area.

let publish = import("publish.rain")

Standard Library

The standard library is just an archive of some Rain source files that are downloaded by the stdlib syntax sugar. There is no special case for the standard library so this technique could be used for other libraries. The only difference with the standard library is this syntax sugar is embedded in the Rain binary so that it doesn't need to be written in each project. The implementation is roughly as follows.

pub let download_stdlib = fn(version) {

url = base_url + version + "/stdlib.tar.gz"

download_result = download(url)

if !download_result.ok {

_throw("failed to download stdlib")

}

lib_area = extract_tar_gz(download_result.file)

stdlib_area = create_area([dir(lib_area, "lib/std")])

load_stdlib(stdlib_area)

}

pub let load_stdlib = fn(area) {

import(file(area, "std.rain"))

}

None of these functions depend on local areas, so for a given version of the standard library this can be cached for a long time. The only part that is a bit unsound is the download. Rain assumes downloads don't change which is not necessarily true. The download cache has an expiry time after which it will request the file again but still use an etag to avoid downloading the whole file. This is another area that needs improvement, as unreliable downloads could result in unexpected behaviour. I think the best solution would be for the caller to provide a checksum for the download so that if it changes an error is created. A lockfile committed to the repository would help solve the usability problem here.

Types

The type system is not finalised but there is a rudimentary system in place. The main idea is that types are just values. Unlike other languages, types don't exist in their own namespace. This has trade offs. The benefit is, all the existing code for evaluating expressions and caching works for types too. The downside is, that type checking becomes more complicated. For the moment type checking is only done at runtime when its value is present. This is fine but means you don't get the benefit of catching errors before running.

let std = stdlib("0.9.1")

let {String, List} = std.types

let main = fn() {

foo

}

let foo: List(String) = [

"abc",

"5",

]

In this case List is a function that takes a type argument and returns a type. Currently internally this is implemented as a type check function but I am looking for a better solution. Here is the implementation of List in std.types. It just checks all the elements match the expected type.

pub let List = fn(inner: Type) -> Type {

fn(v: Any) -> Bool {

get_type(v) == AnyList && fold(true, v, fn(acc, x) {

acc && check_type(x, inner)

})

}

}

I need to do more exploration into the possibilities and limitations of this type system. I have many open questions around this: custom types, function types, static type checking, generics, etc.

Implementation

Lexer

The lexer is very simple. It consumes a stream of UTF-8 characters. It reads these and produces an iterator of tokens. Most tokens are a single character, some are two and a few are more complicated consisting of many characters. Equals =, left paren ( and comma , are all single character tokens. Return type ->, double equals == and logical and && are all two character tokens. This means the lexer is considering one or two tokens at once. String literals, comments and identifiers (variable or function names) are all single tokens but often consist of multiple characters. These are still easy to lex because they have clear starts and ends. There are a few identifiers that are mapped onto keywords and some that are marked as reserved for future use.

Parser

The parser consumes tokens from the lexer and builds an abstract syntax tree. The parser consumes tokens one at a time but there is a flexible peeking API to allow it to read peek ahead N tokens. Currently the most the parser looks ahead is 2 but for expressions this is more complicated. Expressions are more complex since they have unary operators like ! and binary operators like +, || and . that have different precedence. The parser traverses a single source file and creates a tree of nodes that are referenced by their index in a list. It also keeps track of the mapping from the tree to the source file so that errors can be attributed to a line and column. This is also important because none of the text are copied into the syntax tree. Any identifier or string needs to resolve the span in the source file string to get its contents.

Tree Sitter Parser

This all works well and is efficient enough for my purposes currently. However, I like syntax highlighting. In order to have good syntax highlighting the parser needs to execute quickly and be error tolerant. My parser will stop at the first error. So I looked into tree sitter as it is a parser generator designed specifically for editors to do highlighting.

Using tree sitter, you define the grammar using domain specific language JavaScript rules. It then generates a C library and accompanying language bindings. To ensure that these two parsers are as close as possible, I run them both and if my parser accepts an input that tree sitter doesn't, it will return an error. After defining some highlighting rules I was able to get syntax highlighting in my editor and on this page. Eventually I would like to migrate from my custom parser to the tree sitter parser to avoid having two pieces of code that do the same thing.

Runner

The runner takes the parsed abstract syntax tree of each module and runs them. The caller defines the declaration entry point. It finds this and steps through the declaration calling any functions as required and controlling the cache. There is no intermediate representation after the abstract syntax tree, since I wanted to keep it simple and have easy access to the spans. The runner has to keep track of the current module, locals, dependencies, stack trace, closure captures, generated files, etc. The runner is implemented recursively which is not ideal and I would like to change that. This would make it possible to run functions asynchronously. It also exposes a set of internal functions that do provide important behaviour to the standard library.

Rain is split into two main crates, rain-lang and rain-core. rain-lang implements all the language specific features but is designed to not depend on the outside environment at all. This is so that it can be compiled to web assembly and run in the browser. rain-lang exposes a Driver trait that is expected to be implemented with all the operating system specific implementations. rain-core implements Driver for UNIX like and Windows operating systems.

CLI

The command line interface is the main way to use Rain. It's primary usage is to run Rain module by specifying rain exec <declaration> where declaration is the declaration (function or value) to evaluate. It has commands to rain prune and rain clean the Rain cache. It has support for spawning a server process that talks to the CLI client of IPC. This means invoking the CLI multiple times is more efficient since the server can work in the background and hold things ready. It has an --offline flag that can use the download cache more aggressively. There is also a --seal flag to prevent any of the escape APIs being called.

Language Server

All modern languages are expected to have strong editor support these days. As a person who enjoys using language servers when possible, I want to implement a language server for Rain. Language server protocol is specification created by Microsoft. It uses JSON RPC for communication between an LSP client (usually a code editor) and an LSP server. The client passes the source text to the server and the server provides diagnostics and actions. I have implemented a basic language server for Rain. It currently only shows syntax errors by invoking the tree sitter parser. I plan on fully integrating the Rain runner in this so that simple parts can be evaluated and type checked. It could even participate in the same cache as the CLI and CLI server.

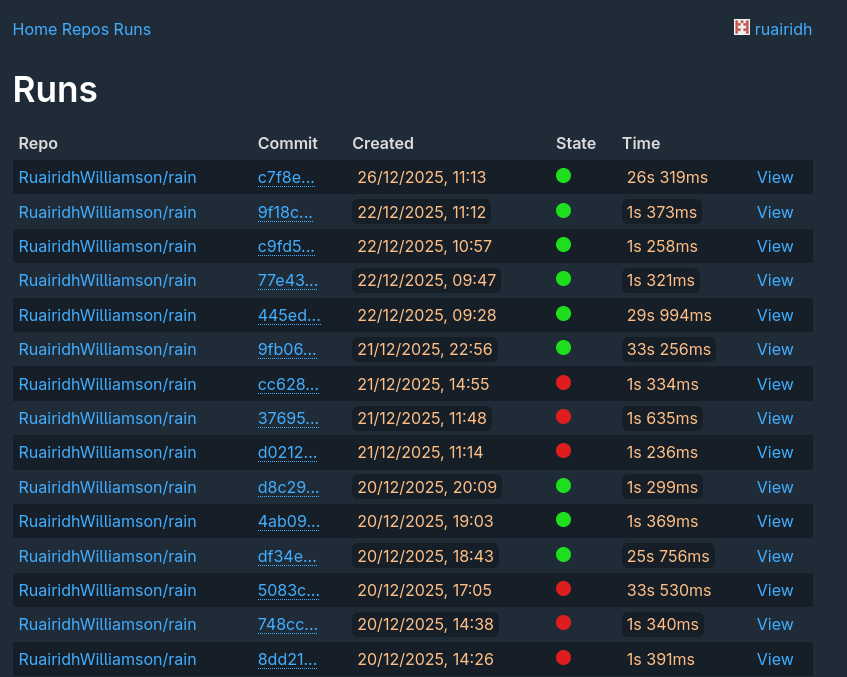

Continuous Integration

Using this I have built a continuous integration server. It consists of two backends. A coordinator/runner and a web interface. They both connect to a Postgres database to share state. The coordinator receives requests to run a Rain script from GitHub or the web interface. The web interface shows all the runs, their statuses and their output. The coordinator uses the GitHub Checks API to show the status on GitHub too. I am currently using self hosting these two services and using it to run the CI for the Rain repository.

The backend services are written in Rust primarily making use of Axum and SQLx. SQLx is really useful for checking SQL queries at compile time against a development database. The services are packed as Docker images and I would like to migrate the building process to Rain. Database migration is handled by a separate service that is run before loading the latest version of the images.

Screenshot of Rain CI Web UI

Future

This is still a work in progress project. Some ideas that I would like to explore further and implement:

- Cache local area files

- Type check a function before calling it

- String interpolation syntax

- Error handling

- Expose functions to add/remove cache dependencies

- Cache cargo compilation

- Lock file

- Generate docs

- Shared cache

- Custom types

- CI artifact storage

- Secret access API

- Docker / OCI image building